A look at the history of medical documentation

Detailed electronic medical records are essential to modern healthcare. We now take for granted the records that doctors and nurses rely on for everything from diagnosis and patient care, to education and compliance. But did you ever wonder where the concept of medical documentation comes from? The practice of keeping medical treatment notes is over 4,000 years old – although medical records have since evolved from paper to electronic.

Today, hospitals and clinics rely on document management systems (DMS) that have been specifically built for creating, updating, tracking, and filing healthcare records. Understanding the evolution of medical records from clay tablets to bits and bytes not only shows their importance in healthcare document management, it also gives us an idea of how to future-proof current digital health records.

# The dawn of medical documentation

Archaeological finds have revealed that the history of medical documentation goes back to the very earliest known writing systems. That’s right – medical information is as inextricably linked to the dawn of communication as it is to healthcare.

The oldest known medical text in the world is a Sumerian clay tablet estimated to be from 2400 BCE. It’s not a case history, but a list of prescriptions, with recipes for making different medicines, salves, and poultices. However, detailed records of medical treatments and observations were most likely being made even earlier, in Ancient Egypt. Unfortunately, papyrus scrolls don’t stand the test of time quite as well as clay tablets, so much of the surviving medical documentation from Egypt is comparatively more recent.

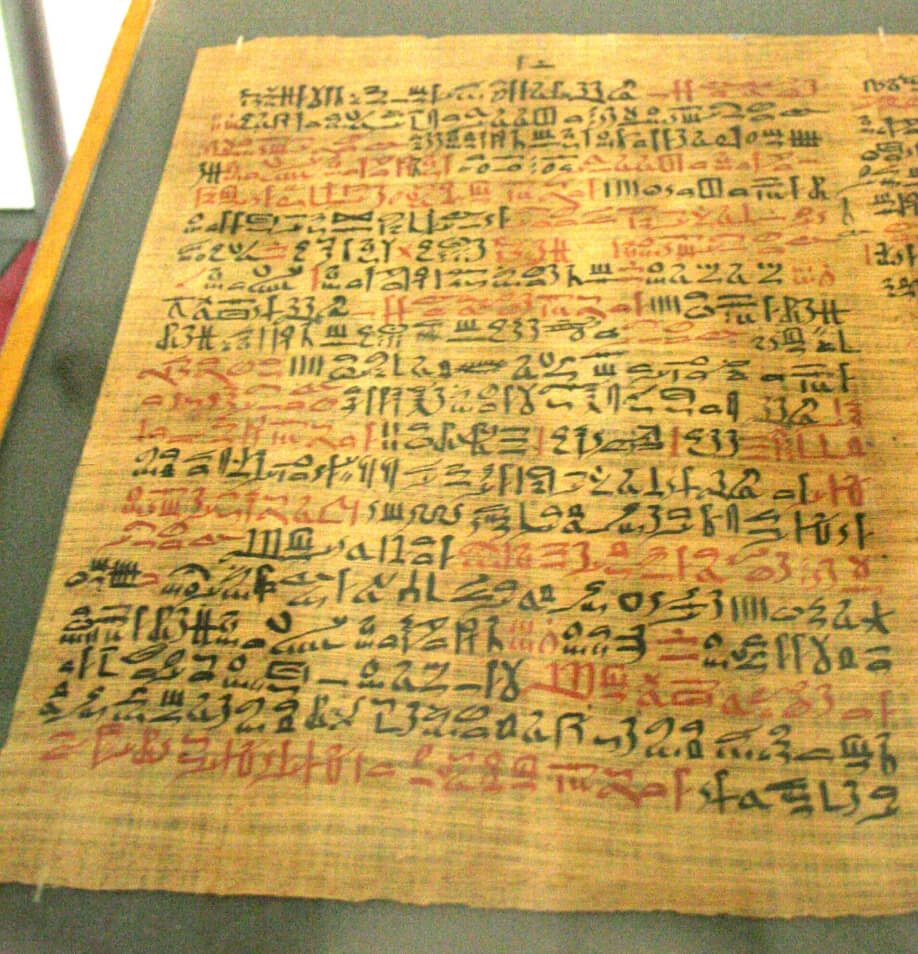

One of the most important Egyptian medical documents is the Ebers Papyrus, dating from 1550 BCE. The 20-meter-long scroll sets out medical recommendations for everything from contraception to burns. There are treatments for physical ailments including migraines and diabetes, along with discussions of mental illnesses like depression and dementia.

As sad as the loss of so many ancient medical texts is, it does demonstrate that medical records need to be durable in order to serve their purpose. Whether they’re written on papyrus or paper, physical records run the risk of being lost or destroyed. That’s why, like so many medical documents created since, the Ebers Papyrus has now been digitized – you can even read it online, translated into English.

But what about something closer to the medical records of today? Not just lists of treatments and medicines, but case histories and patient records. Even those have ancient antecedents.

# Development of traditional medical records

As with so many modern medical practices, keeping patient medical records can be traced back to the Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates (460-370 BCE). Best known today for the namesake Hippocratic Oath, Hippocrates codified a number of medical treatments and kept detailed notes on cases, including the physician’s recommendations, prescriptions, and more.

While much of this ancient medical knowledge went unknown in Europe until it was rediscovered, translated and printed in the 1500s, Arabic physicians built upon earlier Hellenistic practices and continued to innovate with medical records. As director of a hospital in Al Rayy, modern-day Iran, Rhazes (865-925 CE) wrote several medical texts highlighting the importance of regular observation and inspection of patients. A collection of his detailed case histories became one of the most important medical reference books when it was translated into Latin in 1486.

In the 1700s, German doctor Johann Theodor Eller instituted daily observation of patients at Berlin’s Charité hospital, with junior doctors required to write up each patient’s condition and history of treatment. By the early 1800s, a similar system was in place across hospitals and clinics in New York. Within a few decades, keeping medical records was commonplace across Europe and the US.

# Creating integrated medical records

However, all these medical records were still primarily used for educational purposes. They were presented as stories of isolated treatments, rather than fully contextualized patient histories. Patients had no permanent, unified health record that followed them from one doctor visit to the next. Even different wards within the same hospital would keep their own medical records, so finding all the data about a specific patient was hard, and consistent care was rare.

For the first time in the history of medical documentation, but not the last, a new system for storage and retrieval of medical records was needed. In 1907, Henry Plummer solved the problem of all that disorganized data by implementing a single, permanent health record for each patient at the famous Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

Single, integrated files paved the way for standardized medical records to become an essential component of early social health insurance programs. This meant that the creation and editing of medical records now needed to be tracked more closely, especially in case of any legal issues that arose.

In the space of a century, the evolution of medical records saw them go from rudimentary teaching aids to a cornerstone of modern medicine.

# History of electronic health records

After World War II, as medical documentation became standardized and filing systems more efficient, the concept of electronic health records first appeared.

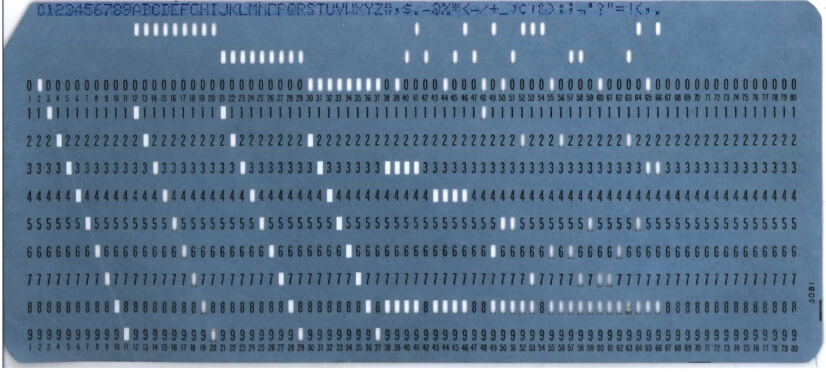

The earliest computer-based medical records were created in the 1960s using punch cards. However, these solutions relied on large mainframe computers, which most clinics and hospitals couldn’t afford, and they made records cumbersome to update. And of course, the punch cards weren’t easily readable, meaning paper records still took precedence.

It wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s, when technology like document imaging, fax machines, and scanners became commonplace, that paper records were digitized on a large scale. Finally, all that medical paperwork could be stored and shared more easily, without having to dig through a room full of filing cabinets.

But digitizing paper documents is only the beginning of the history of electronic health records. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the ubiquity of PCs and digital word processors opened up an entirely new possibility: digital-first medical records.

Hospitals, clinics, and eventually governments realized that the true benefits of digital documentation went far beyond easy storage and retrieval.

Digital medical records don’t rely on people being able to read a doctor’s poor handwriting – infamous for its illegibility. More importantly, they’re fully text searchable, and allow clear tracking and history of both access and edits for compliance and privacy purposes.

Despite the obvious benefits, the adoption of digital-first electronic health records took some time. According to one study in 2009, only 10% of US hospitals had an integrated computer system in place to handle digital medical records. Luckily, the percentage of US hospitals using electronic health records had increased to 80% by 2022.

# Lessons from the evolution of medical records

The evolution of medical records has been a gradual process of discovery, iteration and improvement, as physicians slowly determined what the main purpose of medical documentation was, and how best to manage it. The history of medical documentation also shows that clinics are always moving towards better healthcare document management systems.

# Positives

All quality healthcare document management systems must ensure that health documents are:

-

Durable

Medical records must be able to be safely kept for decades, or even centuries, without becoming damaged or unreadable. For digital medical records, this means backups and file compatibility are essential. -

Easy to retrieve

Just as doctors shouldn’t be expected to run between wards to gather all the information on a patient, they shouldn’t be expected to scroll through endless pages of digital documents to find what they need. Today, fully text searchable digital medical records are a key part of the solution to this problem. -

Complete

Digital medical records should be the single source of truth for a patient’s history of treatment. If any information is missing, it undercuts the value and usefulness of the entire record. -

Easy to update

A major part of ensuring medical records are complete is making them easily updatable. Whether they’re carved into a stone tablet or turned into punch cards, any medical document that’s difficult to edit inevitably becomes outdated quickly. -

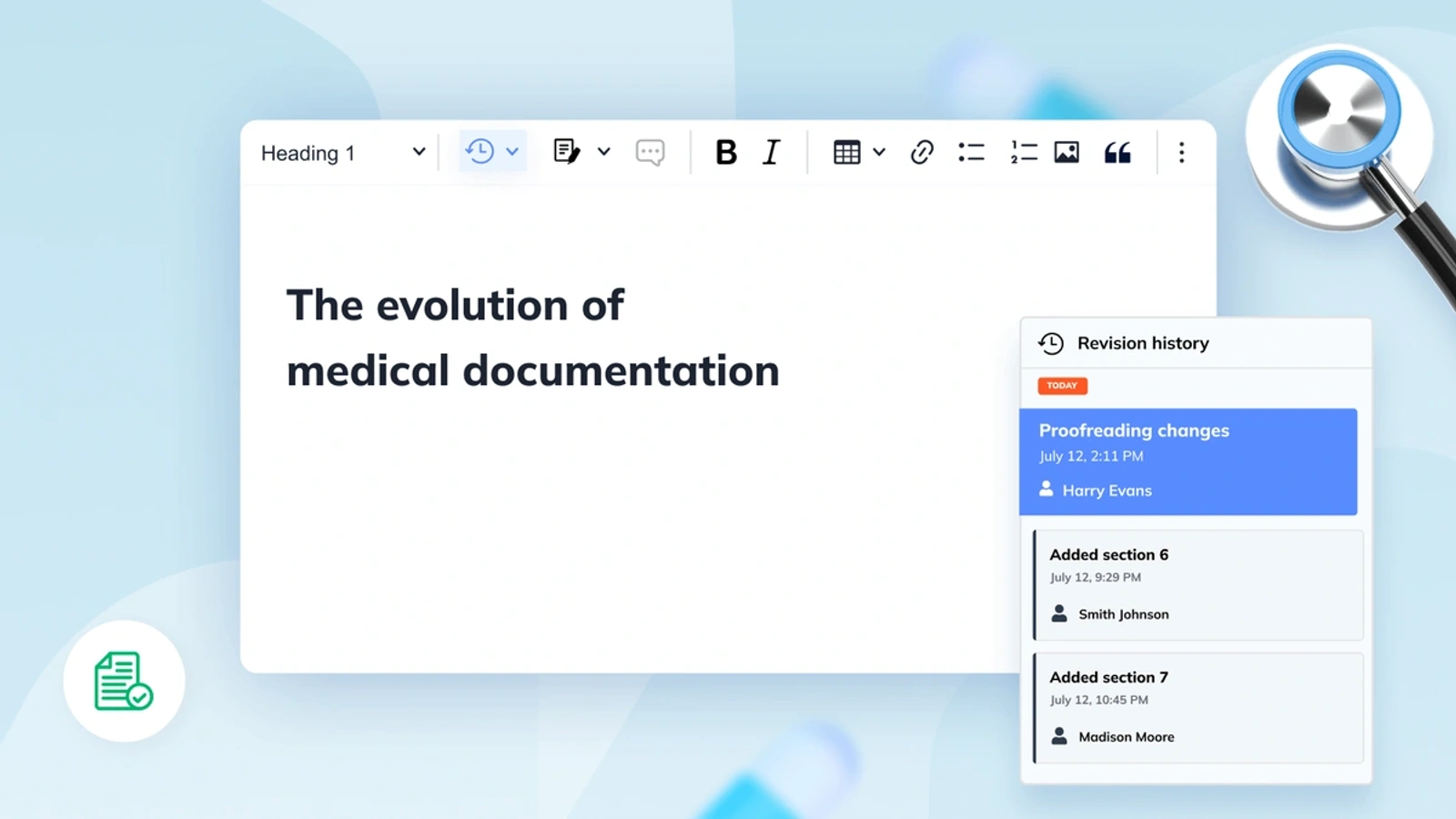

Trackable

Ever since health records became a key part of medical insurance and legal processes, it has been vital to know when, how, and by whom a medical record was edited. Digital medical documentation makes this much easier by automatically tracking edits to documents.

# Negatives

In hindsight, one of the other key lessons from the history of medical documentation is that the latest advances take time to become common practice. The widespread adoption of electronic health records took decades, and it’s still at different stages in different regions and countries.

In the same way, not all medical DMS platforms have kept up with the needs of modern medical professionals. Many DMSs rely on cumbersome, outdated components that don’t support the key features medical practitioners and support staff need.

This is especially true in the case of rich text editors, which are pivotal in creating, updating, retrieving and tracking documents in a medical DMS. All these tasks require you to interact with a rich text editor. And if the editor in your DMS is difficult to use, people won’t get the full benefit of working with electronic health records.

# Take your medical documentation into the future with CKEditor

CKEditor is a modern, collaborative rich text editor with all the must-have DMS features. The familiar word processor interface makes it easy to update and create records. Documents are stored in a flexible HTML format, while powerful file conversion tools including Import from Word and Export to PDF and Word bring compatibility with the most popular file types. Revision History means you can keep track of any changes to a document, for compliance purposes.

Contact us today to learn more about future-proofing your healthcare DMS.

# History of medical documentation FAQs

Ancient civilizations kept medical records in different ways. In Sumeria, they were carved on stone tablets, in Egypt and Greece, they were written on papyrus scrolls, while in Rome, papyrus and parchment were used. Paper medical records using a common format became standard in Europe and the US in the late 1800s.

American physician Larry Weed is generally credited with inventing the first electronic medical record system in the 1960s. Weed’s system focused more on clinical data management and less on creating a full record for each patient.

The first fully fledged electronic health record system was rolled out at the Regenstreif Institute in the US in 1972. However, the system was too expensive for most clinics and hospitals to use, so it didn’t catch on.